Metaphors we live by

“Every age has its own unique view of nature, its own interpretation of what the world is all about. Knowing a civilization’s concept of Nature is tantamount to knowing how a civilization thinks and acts.” (Rifkin, 1983)

"It matters which metaphors we choose to live by. If we choose unwisely or fail to understand their implications, we will die by them." (Romaine, 1996)

Metaphors are one of the main ways through which we conceptualize the world (Verhagen 2008). But, what exactly is a metaphor? In a nutshell, metaphors are linguistic devices that allow us to understand one thing in terms of another. If we say, for example, "She gave us a very warm welcome", we are employing a rather common metaphor: "Affection is warmth". Namely, we use warmth (temperature), which is something very tangible that we can experience in our bodies, in order to understand something more abstract, which is the emotion of affection.

In a seminal book by George Lakoff & Mark Johnson back in 1980, these authors were able to notice that metaphors are employed all the time, in all of human contexts. They found that metaphors are omnipresent in important domains such as politics, morality, philosophy, science, justice, among others. Take for example another metaphor discussed in their book: "Theories (and arguments) are buildings":

Is that the foundation for your theory? The theory needs more support. We need some more facts or the argument will fall apart. We need to construct a strong argument for that. I haven't figured out yet what the form of the argument will be. Here are some more facts to shore up the theory. We need to buttress the theory with solid arguments. The theory will stand or fall on the strength of that argument. The argument collapsed. They exploded his latest theory. We will show his theory to be without foundation. So far we have put together only the framework of the theory.

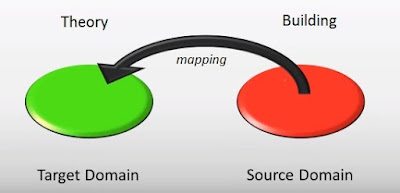

In the very same way as in "Affection is warmth", here we understand something that is quite abstract, i.e. a theory, in terms of something very concrete and tangible for us, the structure of a building. The tangible aspect of the metaphor, in this case the building, is called the source domain, and its characteristics are mapped onto what is called a target domain, which corresponds to a theory in this example. This is represented in Figure 1. Naturally, in order so that the mapping between both domains can properly function, there needs to be a certain degree of correlation between the kinds of things that happen in both the source domain and target domain. In our case, theories can be treated as buildings because they need evidence and support for the ideas they convey. If arguments in a theory can be proven wrong, then these arguments are not "solid", so the theory loses its "foundation" and hence it can "fall apart". Since the things that happen to buildings are similar to the things that happen to theories, the mapping of this conceptual metaphor is effective to be able to talk about theories as buildings.

Figure 1. Conceptual metaphor

After more than 30 years of work since the publication of this book, the contemporary theory of metaphor (Lakoff, 1993) is one of the most robust discoveries in the field of cognitive linguistics. Metaphors have been found to be actually one of the main devices through which we can think and communicate in language.

But when it comes to our ecological interests, we might wonder: Is nature subject to metaphors? Indeed, it is. Metaphors of nature are of utmost importance, since they communicate and construe the meaning of nature, the place of humans in nature as well as normative ideas about what kind of relationship humans should have towards nature. Metaphors of nature have historically been present since the beginnings of western civilization, and they embody different worldviews and ways of understanding and treating nature (Verhagen, 2008).

In previous articles, we have examined two main metaphors of nature, "Nature is a resource" (this post and this one), which is used mainly in modern societies, and also the metaphor "Nature is family" (in this post), from a non-modern community. As we were able to notice in those articles, these metaphors have radically different ethical consequences about the ways in which we understand what nature is and the way we should treat it.

However, these are not the only existing metaphors of nature. Francis Verhagen (2008) has also identified the anthropocentric metaphors of "Nature is a machine" and "Nature as Scala Naturae" as well as the more ecologically relevant, biocentric metaphors of "Nature is a web" and "Nature as measure".

As a mode of conclusion, I wanted to introduce you to conceptual metaphors in order to get a grasp onto how these are permanently used in language and how they can shape specific worldviews, specially when it comes to nature. As an example, the "Nature is a resource" metaphor has become so widespread in modern societies that it is now a matter of common sense to say that "humans exploit natural resources", it has become a kind of unquestionable truth. It is thus of utmost importance to analyse this and other existing metaphors about nature in order to understand what they entail in terms of ethical values and practices that contribute to the ecological crisis or that can help to address it.

References

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor.

Rifkin, J. (1983). Algeny: A New Word, a New World.

Romaine, S. (1996). War and peace in the global greenhouse: Metaphors we die by. Metaphor and Symbol, 11(3), 175-194.

Verhagen, F. C. (2008). Worldviews and metaphors in the human-nature relationship: An ecolinguistic exploration through the ages. Language and Ecology, 2(3), 1-18.

In previous articles, we have examined two main metaphors of nature, "Nature is a resource" (this post and this one), which is used mainly in modern societies, and also the metaphor "Nature is family" (in this post), from a non-modern community. As we were able to notice in those articles, these metaphors have radically different ethical consequences about the ways in which we understand what nature is and the way we should treat it.

However, these are not the only existing metaphors of nature. Francis Verhagen (2008) has also identified the anthropocentric metaphors of "Nature is a machine" and "Nature as Scala Naturae" as well as the more ecologically relevant, biocentric metaphors of "Nature is a web" and "Nature as measure".

As a mode of conclusion, I wanted to introduce you to conceptual metaphors in order to get a grasp onto how these are permanently used in language and how they can shape specific worldviews, specially when it comes to nature. As an example, the "Nature is a resource" metaphor has become so widespread in modern societies that it is now a matter of common sense to say that "humans exploit natural resources", it has become a kind of unquestionable truth. It is thus of utmost importance to analyse this and other existing metaphors about nature in order to understand what they entail in terms of ethical values and practices that contribute to the ecological crisis or that can help to address it.

References

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor.

Rifkin, J. (1983). Algeny: A New Word, a New World.

Romaine, S. (1996). War and peace in the global greenhouse: Metaphors we die by. Metaphor and Symbol, 11(3), 175-194.

Verhagen, F. C. (2008). Worldviews and metaphors in the human-nature relationship: An ecolinguistic exploration through the ages. Language and Ecology, 2(3), 1-18.

Comments

Post a Comment