Questioning the “exploitation of natural resources”

Text translated by Louise Nicolas-Sourdot

Texte traduit par Louise Nicolas-Sourdot

A few weeks ago, I started

working on an analysis of French secondary school textbooks and how they portray the relationship between humans and nature.

Particularly, I examined an Earth and Life Sciences textbook for 6th

grade, and I obtained rather surprising results that I'm sharing with you in this post.

In this textbook, the

relationships between humans and nature are a rather secondary subject. Nonetheless,

when these relationships are addressed, it is through the idea of the “exploitation

of natural resources”. Apparently, one of the main learning objectives for the Earth

and Life Sciences program in French secondary school is the understanding of the “impacts

of the exploitation of natural resources”.

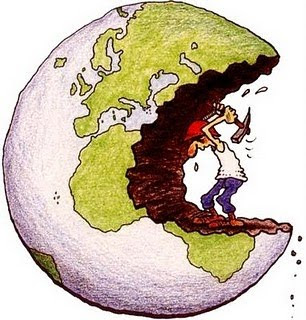

What I would like to illustrate

in this text is that this notion is far from being neutral, it symbolizes a strictly utilitarian and objectifying vision of nature, that is quite characteristic of western culture. These are values at the root of the current ecological crisis.

Firstly, speaking about the "exploitation of natural resources" creates a specific frame

for understanding human-nature relationships, a frame which evokes the understanding that “nature is a collection of resources” (Gudynas, 2010). In this understanding,

nature is an ensemble of resources that can be extracted and used to serve

humans. The main point is that this is the only kind of relationship that is recognized, so that any other kind of relationship, such as admiration for nature, nature as a source of meaning and as a source of improved mental health, are absent, and in this way they are not taught to children and adolescents. All they receive is the understanding that we humans exploit natural resources and that is all there is to it.

Let us take a closer look.

Firstly, the notion of exploitation means “to use something to one’s advantage”

(Larousse). Likewise, the verb “to use” can be defined as “to make something

useful; to serve to an end”. This situates us instantly in a utilitarian

frame, in which our relationship to nature is conceived as being

unidirectional: nature serves humans, and never the other way around. Reciprocity is a value that has been found to be central in certain indigenous communities, for example those of North America (Harris and Wasilewski, 2004). Reciprocity is a value in which relationships are thought to be bidirectional in order to be balanced, in the understanding that unidirectional relationships tend to work for the detriment of one of the parties and the benefit of the other. This is commonly what happens in people with narcissistic disorder, they treat other people as means for their own ends and do not believe that they have to give something back in order to balance the relationship or reach a certain harmony.

In addition, the concept of "natural resources" can be analyzed by means of the linguistic

notion of “the trace” (Stibbe, 2015). The trace

happens when a discourse represents the living world in a way which

obscures it and conceals it, leaving just a faint trace rather than a vivid

image. In this case, we

may think that “somewhere” in the concept of “natural resources” - but hardly

noticeable – there are trees, birds, bees, foxes, etc.; intentional subjects

living their own lives. However, describing them as natural resources makes us think of them more as a pile of inert objects, such as a mining site that we extract.

On the other hand, the concept

of “natural resources” can also be analyzed as a mass noun. A mass noun is an abstract concept that

generalizes and homogenizes a group of entities. Arran Stibbe (2015) states

that “when trees, plants and animals are represented in mass nouns, they are

erased, becoming mere tonnages of stuff.”

If we think about it, whenever

we speak about “resources”, it naturally relates to complements of

quantity: “abundant resources”; “scarce resources”; “depleted resources”. For

this reason, moral judgments associated with “resources” are made in

quantitative terms. In other words, when resources are abundant it is good, and

when resources are depleted it is bad. In the same manner, “exploiting natural

resources” becomes the normal and acceptable act, and “overexploiting natural resources”

becomes a morally reprehensible act. In doing so, the hidden “trace”

is the fact that whenever activities of “natural resource extraction” are executed,

animals and plants are killed, at the same time as their habitats are destroyed.

Furthermore, for many people

nature is beautiful, it deserves respect, and it is also a source of

inspiration. In other words, there are not only quantitative values but also qualitative values that are associated with the contributions of nature and ecosystems to our life quality. When speaking about “resources”, those emotional and aesthetic

relationships are cancelled. It is

semantically not possible to speak about a “beautiful resource”, a “resource

that deserves respect”, and even less about an “inspirational resource”.

To sum up, talking about “the

exploitation of natural resources” implies treating nature as an object that

can be manipulated and used in order to serve humans’ interests (Gudynas, 2010).

This notion establishes a one-way relationship between us and nature, in which

we can profit from the services it provides us without having to reciprocate. Moreover,

by reducing nature to an object, we forget about the fact that nature is

composed of conscious beings, who want to persevere in their existence.

In this way, middle-schoolers

throughout France are taught that the essential way to relate with nature is by

exploiting it as we please. In so doing, this type of language reproduces and

reinforces one of the main values at the root of the current ecological crisis.

References

Gudynas, E. (2010). Imágenes, ideas y conceptos sobre la naturaleza en América Latina. Cultura y naturaleza, 267-292.

Harris, L. D., & Wasilewski, J. (2004). Indigeneity, an alternative worldview: Four R's (relationship, responsibility, reciprocity, redistribution) vs. two P's (power and profit). Sharing the journey towards conscious evolution. Systems Research and Behavioral Science: The Official Journal of the International Federation for Systems Research, 21(5), 489-503.

Stibbe, A. (2015). Ecolinguistics: Language, ecology and the stories we live by. Routledge.

Comments

Post a Comment