Partiality in the ontology of mesology

By Rodrigo Cáceres

This article aims to articulate and develop an

immediate consequence of the mesological perspective (Uexküll’s Umweltlehre,

Watsuji’s fûdogaku, Berque’s mésologie) concerning the concept of partiality

and its correlates of inclusion and exclusion.

Introduction

The mesological perspective is a paradigm or

epistemological perspective that attempts to go beyond the dualisms that

characterize western modernity in order to recosmize our place within mediance,

i.e. the structural moment of our human existence. In other words, its

purpose is to reintegrate the unity of the dynamic coupling and concrescence

(growing together) of the individual with its surroundings. This mesological

horizon appears as a deep criticism of the notion of an ‘objective universe’ of

objects ‘in themselves’ which has taken hold of the western imaginary since the

scientific revolution. The same development towards abstraction has also taken

place from the side of the subject, mainly through Descartes’ res cogitans, the

thinking substance which is independent from its milieu. Against these developments

towards the abstraction of both subject and object, alienating them from each

other, mesology’s aim is to reconcretize or synthesize the unitary character of

mediance, where both subject and object are connected and in constant mutual

configuration.

Among mesology’s main concepts we find certain

neologisms such as ‘trajection’, ‘trajective chains’, ‘mediance’,

‘concrescence’ and ‘medial body’, concepts that are not trivial or easy to

grasp, but rather -one might say as the Buddha spoke of his dharma- they are

‘difficult to see’ (dudaso in Pali). Indeed, Berque finds himself in the

need to create these concepts in order to denote something for which there was

no word available, so it may well be that as Westerners we are not logically prepared

to think in these meso-logical terms, our way of thinking having been greatly

shaped by the Greek concepts of ‘essence’, ‘substance’, ‘nature’, ‘attributes’,

‘faculties’, etc. which tend to separate, distinguish and abstract phenomena

from their integrated character within the experiential milieu where they

concretely take place.

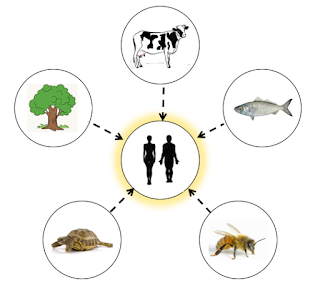

One of the foundational ideas of mesology is an

ontological distinction that does not exist in common language: the distinction

between environment (Umgebung) and milieu (Umwelt). This

distinction, advanced by the

German naturalist Jakob von Uexküll, denies that we are confronted to an

objective reality which we ‘recover’ or ‘represent’ inside our minds, but

rather it proposes that we are confronted to a milieu of signs (Umwelt)

that are configured or composed by our organism as the result of a contingent

history of selections of components of a common given environment or Umgebung.

In practice, this means that for all individual subjects, their surrounding

worlds are their own worlds, in the sense that it is their internal

organization which brings forth the signs with which they interact on a daily

basis.

Mesology’s notation for reality

One way of introducing the mesological

perspective is through a careful examination of its logical-mathematical

notation of reality, in which all these neologisms and concepts are

articulated:

Where r is reality, ‘S’ is the logical subject which

in this case denotes the environmental datum or Umgebung, ‘P’ denotes

the logical predicate, ‘I’ denotes a first-person perspective, ‘I’ denotes the individual

concerned and the ‘/’ denotes the existential trajector ‘as’ (en tant que).

P’ and P’’ are further trajections of the original trajection (S/P), meaning

that trajection is a recursive and unfinished process which may well continue

if the conditions for its occurrence are met.

We can note first that this formula constitutes a

multirealism, where reality is specific to the living species concerned, since each

species take certain aspects of the environmental datum and translate them into

a certain predicative field or milieu of meaningful signs which ek-sist (stand

out) to a certain first-person perspective I. If we take into consideration the

ontological distinction between Umgebung and Umwelt, then this notation of

reality has both chronological and genetic aspects, since it denotes how

reality appears historically on the basis of an already existing objective universe

or Umgebung. The Umgebung in itself as a physical or objective

domain is -before life appears on this planet- closed or concealed upon itself,

it is not disclosed nor made apparent. What life does, what living beings add

to the Umgebung is that they take it and disclose it (Heidegger’s Erschlossenheit)

by signifying it, they create an opening -just like a wound which creates a

certain depth- which is the place where the Umgebung is translated or

trajected into a certain milieu.

In a very apt metaphor for this process of trajection

or translation, Thure von Uexküll explains that “Nature may be compared to a

composer who listens to his own works played on an instrument of his own

construction. This results in a strangely reciprocal relationship between

nature, which has created man, and man, who not only in his art and science,

but also in his experiential universe, has created nature.” (von Uexküll,

1992).

In this logical principle of trajection, where reality

is neither the subject in itself (S) nor the predicate in itself (P) but

specifically the subject in terms of the predicate (S/P), we can also

see a principle of ordinality or nestedness, that complexity science renders

through the idea of an emergent dynamic, defined by Terrence Deacon as: “one in

which particular configurations of constraints on possibility result in

unprecedented properties at a higher level. Crucially, however, something that

is emergent is never cut off from that from which it came and within which it

is nested because it still depends on these more basic levels for its

properties”. (cited by Kohn, 2013, p.55) In the case of the mesological formula

for reality, one must note that the predicate (P) is both ontologically novel

and ontologically distinct from the subject, nevertheless both the subject and

the predicate are connected by the existential trajector ‘as’, thus they are

never cut off from each other.

In sum, there are actually two levels to this formula

of reality. First there is the genetic level, namely the trajection or

translation of an objective Umgebung, where it must be noted that in the

logical formula both ‘S’ and ‘/’ are not phenomenally visible, since ‘S’ in

itself is always concealed upon itself or unapparent. Moreover, the process of

trajection, where S is taken and translated into a certain predicative field is

also not perceivable, since the place or the level of sign awareness, where the

understanding of understanding begins is the place of mediance, the place of

the first-person perspective facing a field of meaningful signs. This is the

second level of this formula of reality, namely the result of this trajection,

which is mediance. The two aspects or ‘halves’ of the resulting mediance are

(1) the predicative field of signs and (2) the one or “I”, the first-person

perspective for whom these signs are apparent. In the case of humans, among the

signs apparent to a human first-person perspective we find ‘private signs’ such

as sensations of hunger, muscular tension, thirst, tastes, smell, which

characterize our ‘animal body’ as well as ‘collective signs’ such as

conventions, norms, institutions, money, etc. which characterize our ‘medial

body’.

Selection and partiality

What does it mean for an Umwelt to be partial? In his description of the relationship

between milieu and environment, Berque states that “the Umwelt is a selection that leaves aside most of the components of

the Umgebung.” Similarly, in 1954

Aldous Huxley wrote the following speaking of the function of the nervous

system:

I find myself agreeing with the eminent

Cambridge philosopher, Dr. C. D. Broad, "that we should do well to

consider the suggestion that the function of the brain and nervous system and

sense organs is in the main eliminative and not productive." The function

of the brain and nervous system is to protect us from being overwhelmed and

confused by this mass of largely useless and irrelevant knowledge, by shutting

out most of what we should otherwise perceive or remember at any moment, and

leaving only that very small and special selection which is likely to be

practically useful.

As we know, selection is a non-linear phenomenon which

simultaneously entails inclusion of the selected part and exclusion of the

non-selected part. Partiality, inclusion and exclusion are thus a direct

consequence of the fact that the living being’s self-organization must make

decisions on which elements of the Umgebung are deemed relevant and

which it will leave out of consideration. For Uexküll’s Umwelt-research this is

of great importance because it means that the Umwelts of non-human subjects

–that Uexküll understood as ‘invisible worlds’- can present signs which are

absent in the human Umwelt, such as infrared radiations, sonar perception,

magnetic field perception, etc. that as humans we are not able to know. In this

manner, the world that an organism spontaneously constitutes is a partial world

with reference to the scope of available components of the Umgebung.

At this level of the presence of qualitative signs

(such as colors, shapes, smells, sounds, magnetic fields), this issue of the

partiality of trajections/translations may not seem to raise ethical or

practical issues. However, the issue of partiality becomes problematic with the

emergence of languages, especially because of our philosophical ambitions to

achieve universality and objectivity. As I have argued elsewhere, languages emerge

as recursions of already existing human mediances (the dynamic coupling of individuals

and their milieu) that before language are for the most part constituted by

qualitative (iconic) and indexical signs (see Kohn, 2013).

Partiality also operates in language because, for a

significant part, language functions as a sophisticated way of pointing.

However, we know that pointing is basically selection, which is marked by

partiality. Whatever is pointed at is necessarily determined by that which is

not pointed at, what is left aside, out of consideration.

At a trivial level, Lakoff & Johnson (1980)

discuss partiality in the case of simple categorizations:

A categorization is a natural way of

identifying a kind of object or experience by highlighting certain properties,

downplaying others, and hiding still others. [...] To highlight certain

properties is necessarily to downplay or hide others, which is what happens

when we categorize something [...] we focus on certain properties that fit our

purposes. Focusing on one set of properties shifts our attention away from

others. For example:

I've invited a sexy blonde to our dinner

party.

I've invited a renowned cellist to our

dinner party.

I've invited a Marxist to our dinner

party.

I've invited a lesbian to our dinner

party.

Though the same person may fit all of these

descriptions, each description highlights different aspects of the person.

Describing someone who you know that has all of these properties as "a

sexy blonde" is to downplay the fact that she is a renowned cellist and a

Marxist and to hide her lesbianism. (p.163)

This kind of trivial categorization may not seem to

carry significant consequences. However, the categorizations of theoretical and

mathematical systems can be of great practical consequences. Ecolinguistic

research, for example, has provided deep analyses of how mainstream economic

theory -taught in most universities around the globe- categorizes nature and

non-human living beings (Stibbe, 2015). Within this theoretical-linguistic

construct, the main categories used to speak of the environment are ‘natural

resources’, ‘natural capital’, ‘ecosystem services’ or ‘natural stocks’, that

portray nature as a stock of resources to be exploited for economic gain. Resources

are things that humans use for their benefit, we think of resources in quantitative

terms (as in abundant, scarce, depleted) and we do not think of resources in

qualitative or even emotional terms. The resource frame necessarily downplays

the idea that nature is full of living beings with intentions, desires and

their own milieu that impacts their overall wellbeing.

This ‘nature as resource’ linguistic trajection or

translation is of common and implicit understanding among economists. However,

as a partial linguistic translation, it leaves out of consideration alternative

trajections of nature, such as ‘nature as kin’, ‘nature as source of admiration/joy/mental

health’ or ‘nature as source of life meaning’ (van der Born et al, 2018).

These alternative trajections bring forth ideas related to respect and

reciprocal relationships with the natural milieu, which are absent in the

objectifying frame of nature as mere resource.

Furthermore, when this linguistic construct is translated

or trajected into mathematical notation, nature disappears altogether. This is

the case in the general equation for the ‘production function’, which is used in

economics to study the behavior of the firm as well as the national product or

GDP. The equation is Y = F(K,L) where Y is the number of units produced (the

firm’s output), K the number of machines used (the amount of capital), and L

the number of hours worked by the firm’s employees (the amount of labor). As is

evident, in this notation there is no sign for whatever material is used to

produce the output, meaning that units are produced out of nothing! As Williams

and McNeill (2005, p.8) explain: “Raw materials used as inputs in the

production process, and any other services provided by the natural environment,

were omitted from consideration altogether. Amazingly, they still are. First

year economics students are still taught in almost all of the currently popular

textbooks that businesses manufacture their products using only labour and

machines!”. In other words, in the linguistic Umwelts of economists and

economics students, non-human beings and ecosystems are permanently excluded

from consideration other than as resources for economic growth and, when

mathematics take central stage, nature disappears altogether, and we are

confronted with an economy which is completely abstracted from the materiality

of the Earth.

Considering that mainstream economic theory and its

concepts are one of the main narratives that organize modern society (Stibbe,

2015), one must also note their attempts to universality and objectivity, which

are apparent in their usual reliance on complex mathematics as well as on metaphysical

claims such as ‘economic actors are profit-driven’, ‘economic actors are

rational’, ‘resources are scarce’ and ‘human needs are infinite’. However, the

general circumstance is that every linguistic model of a milieu is necessarily

partial, since partiality is a direct and unavoidable consequence of the

phenomenon of trajection (and in this particular case, linguistic and also

mathematical trajection).

In summary, discourses and theories in language are

necessarily always partial, in the sense that these are linguistic models that

incorporate and commit to a limited set of concepts that highlight certain

aspects of what occurs in the world in a specific way. When discourses do so,

they implicitly erase all aspects of what they do not take into consideration.

In other words, highlighting something in a discourse necessarily implies

downplaying other things. The issue is that since discourses are positive, whatever

is erased and downplayed by them remains invisible.

Another aspect that is worth mentioning concerning the

partiality of discourses and theories is that we seem to be only able to speak

about this phenomenon through conceptual metaphor, which is the most common

form of trajection in language. In other words, we cannot think about this

phenomenon with literal concepts. A simple overview of the concepts used to

speak about partiality gives us the following list: 'highlight', 'background',

'foreground', 'reveal', 'hide', 'bring to light', 'focus', 'downplay', 'shed

light upon', 'hidden side', 'visible, 'invisible', 'shift attention away from',

'apparent side', 'blurred' and 'erased'.

We have on the one hand the light/darkness metaphor,

where the 'highlighted' aspect, the one that a discourse 'brings to light' or

'sheds light upon' is the aspect that the chosen words or symbols convey. The

'obscured' or 'occult' aspects are the ones not taken into consideration by the

choice and framing of words or symbols.

We have also the vision and glasses metaphor (that function

together), where the 'visible' aspect is where the 'focus is on' and the 'invisible'

aspects are the one where our attention is not focused on, the choice of words

'shifts our attention away' from these 'unapparent' aspects. In the special

case of the glasses metaphor, the aspects not considered can be 'blurred' or 'out

of sight'.

There is then the foreground/background metaphor,

which is also an aspect of our vision, where the salient aspects are the ones

'brought to the forefront/foreground' and the aspects not considered are

'backgrounded' or 'left in the background'.

The reveal/hide metaphor is also present, where the

aspects that are 'manifest', 'revealed' or 'shown' through the choice of words

simultaneously 'hide', 'conceal' or 'cover up' the aspects that are not

considered.

Finally, in the coin metaphor, what is salient is on the

'apparent side' while simultaneously the opposite side of the coin, the 'hidden

side' or 'dark side' (a blend with the darkness metaphor) is not apparent or inaccessible

to sight.

A concluding remark

This multiplicity of ways of trajecting or translating

the phenomenon of partiality is helpful to illustrate the purpose of this

essay, which was to ‘highlight’, ‘bring to the foreground’ or ‘make manifest’

the relevance of the concept of partiality for mesology and its related

concepts of ‘inclusion’ and ‘exclusion’ or -as Arran Stibbe likes to call them-

‘salience’ and ‘erasure’ patterns (Stibbe, 2015). This also entails that the

mesological framework itself is also partial (as it is made of words). There is

one sense where this partiality implies that mesology is a work in progress

aiming for further recognition of the diversity of concrescent motions of

individuals with their surroundings.

However, more generally one needs to consider what von

Uexüll (1992) labels as the phenomenon of homomorphy: “a fundamental

principle which recurs on different levels of complexity, in different ways,

yet always in basically the same form”. Is not trajection precisely a

homomorphic phenomenon? It appears as the principle of world disclosure (S/P)

as well as the principle of linguistic trajection (S/P)/P’ and also in what is

referred to as conceptual metaphor ((S/P)/P’)/P’’ and even in mathematical

trajection ((S/P)/P’)/P’’. Why the identification of homomorphic phenomena is

of such importance for science and mesology is a question that I will not

discuss in this article. However, as it may be evident at this point, this

phenomenon of trajection or translation or metaphor is concretely functioning

more as a verb rather than as a noun. ‘To traject’, ‘to translate’ or ‘to

metaphorize’ is the action “which endlessly brings (pherei) reality

further (meta) than identity.” (Berque, 2016).

References

Berque, A. (2016). Nature, culture: Trajecting beyond

modern dualism. Inter Faculty, 7, 21-35.

Huxley, A. (1954). The Doors of Perception. New

York. Harpers.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we

live by. Chicago/London.

Stibbe, A. (2015). Ecolinguistics: Language, Ecology

and the Stories We Live By.

van den Born, R. J., Arts, B., Admiraal, J., Beringer,

A., Knights, P., Molinario, E., ... & Vivero-Pol, J. L. (2018). The missing

pillar: Eudemonic values in the justification of nature conservation. Journal

of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(5-6), 841-856.

von Uexküll, T. (1992). Introduction: The sign theory

of Jakob von Uexküll. Semiotica, 89(4),

279-316.

Williams, J. B., & McNeill, J. M. (2005). The

current crisis in neoclassical economics and the case for an economic analysis

based on sustainable development.

Comments

Post a Comment