Beyond left and right: Laterality and verticality in the political imagination

By Rodrigo Cáceres

We are

animals of conventions and we know this because it is relatively intuitive for

us. We know for example that the colors of the traffic lights mean what they

mean not because there is an inherent relationship between red and stopping or between

green and moving forward. Their meaning is given simply because at some point a

group of people agreed that it would be so, that these three colors would be

chosen and that each would mean each thing. It is nothing more than a

convention, an agreement or pact between people.

We actually

live in a world of conventions: letters are conventions, words are conventions,

nations are conventions, states are conventions, political-administrative

boundaries are conventions, laws are conventions, the police is a convention,

parliamentary systems are conventions, and a very long etcetera.

In the

political domain, one of the things we have done by convention for more

than two centuries is to think and talk about political ideologies in terms of

laterality or horizontality: we talk about the left, center and right. This

scheme was born in 1789 in the context of the French revolution and has

subsequently spread to the rest of the world, remaining basically unchanged up to our current time.

In this

schema we think and place people and political parties as if they were points

on an imaginary horizontal line, which allows us to talk about things like the

"extreme right" and the "extreme left." This makes sense

since the lines have extremes on each side. Horizontal lines are schemas that we

can use to think about the symmetric wings of a bird, which is why it makes sense to speak of “right-wing” ideas or “left-wing” ideas. In a general sense, in our worlds we are caught up in a way of

thinking in which political ideologies are spoken and imagined in terms of

horizontality.

Our

personal problem from being raised in a culture that lives through this

convention is the problem of preferences: Which is better, left or right?

Unfortunately, as it is a convention - like the traffic light - the terms

"left" and "right" have no inherent relation to what they mean in (political)

practice, so a priori it is not obvious to know what are the "right-wing

ideas" and the "left-wing ideas". Who do they favor? What are their

beliefs and preferences?

What we can

do to know which to prefer from the two is to use other aspects of our lives as

guides. On the one hand, we have familiar sayings that tell us things like

"all extremes are bad" and that we have to "maintain balance or

equilibrium" or reach a "just middle".

On the other

hand, when we talk about morality, we talk about a “righteous” person to refer

to someone that is correct, honest, honorable, etc. In English-speaking

countries, "right" means good, correct, true, true, fair and adequate, all being words that represent things that we generally prefer:

being fair, good, correct, etc.

In

addition, approximately 90% of the world's population is right-handed, and in

general the right hand is the "good hand" in many languages and

cultures. Traditionally the left hand has been called "sinister",

"the hand of the devil", and left-handed people have been forced to

repress their left-handedness.

Daniel

Casasanto, a psychologist at the University of Chicago, studies how the western

world is mentally biased to the right. He has shown that our handedness or

manual prevalence unconsciously influences many of our preferences and

decisions: the people we vote for, the things we buy, etc. According to

Casasanto, this would be a bodily-based natural influence since it occurs from a very early age. In one of his scientific articles, he explains that "from an

early age, right-handers associate rightward space more strongly with

positive ideas and leftward space with negative ideas, but the opposite is

true for left-handers." The fact that we live in a culture where the right

is usually good, would simply be a consequence of the fact that right-handers are a

majority: the cultural manifestation of a majority force which manifests itself through how their right-handedness influences their

way of thinking.

Summarizing

this cultural bias to the right, he explains that "if people conceptualize

good and bad things in a left-right continuum in the manner dictated by their

culture and language, then everyone should think that right is good."

Moreover -

and returning to the political topics - psychologist Stewart McCann showed that

in the United States (where the left/right duality equals the Democrats/Republicans duality), States with a higher percentage of right-handed people tend to be more

Republican and that States with a higher percentage of left-handed people tend

to be more Democrats.

In this

way, we understand that this type of unconscious influence of a majority of right-handed people suggests that

it is good to hold "right-wing" political ideas, regardless of what these ideas are. This bias towards the right is more

profound in English-speaking countries since for example in Spanish "right"

(derecho) does not mean things like

"true", "good", “correct”, “adequate” or "true".

What would

happen if the left-right scheme was actually inadequate to think about our

current situation?

It is

necessary first that we notice that this horizontal scheme is reproduced and

constantly recreated in our culture through language. It is a conventional

reality, that is, it is something that is real only because we speak in these

terms on a daily basis. What usually happens with conventions is that people

are totally unaware that they are using a convention or agreement. But since they are nothing more than conventions, they can be questioned and changed if they are found not to be adequate.

In other

words, people who live in conventions such as the left-right scheme, live in

the implicit acceptance of this scheme as something valid or real, simply

because if they did not accept it they would not use it for talking. The main point is that we do not perceive conventions as conventions, we perceive them as effective instruments

that allow us to refer to certain issues. In this case, the effectiveness of

the left-right linear scheme is that it allows us to talk about the topic of

politics thanks to its very simple linear structure that has extremes, a center and points

on the line.

Why would

the left-right scheme not be adequate?

We saw on

the one hand that our innate handedness biases our culture to the right, since right-handed

people are the vast majority. On the other hand, what is most evident to

consider is that we live in hierarchical societies, and that hierarchies are

schemes that we understand in terms of verticality: as a vertical line in which

there are people or groups above, those who have the power and the authority,

and then those below, who are usually the exploited, manipulated and abused by

those who are above.

From this perspective it seems at least strange (to more than one it might seem idiotic) that we understand politics - and therefore, the organization of society - in horizontal terms when we actually live in a vertically structured society.

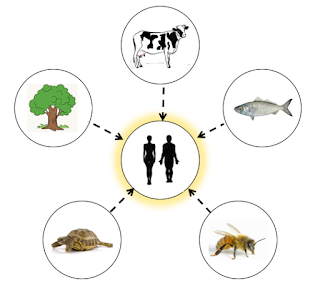

Actually,

thinking about politics in terms of verticality is much more intuitive: "Up-level

ideas" are naturally ideas that favor powerful groups in society, while

"Down-level ideas" are ideas that favor those who they are not

powerful and those who are unable to politically represent themselves: children, the poor, the

elder, those who are sick, marginalized, excluded, etc. The inability to represent one's interests and the consequent lack of consideration is probably deepest when it comes to the exploitation of

rivers, oceans, forests, land and the animals and plants that live there, whose

well-being is systematically ignored in our societies.

In this sense, thinking in terms of verticality indirectly makes us note that in the current

left-right scheme, both the left and the right explicitly or implicitly accept

extractivism, industrialism and speciesism, by systematically refusing to

consider the welfare of nature through treating it as something that must be

permanently exploited. And these are the beliefs that are provoking the current planetary

ecological crisis.

We can also

note that the implicit preferences of those who prefer Up or Down become more

transparent. On the one hand, we would know that those who hold Up-level ideas prefer

that there are certain groups that hold the power and decide on the organization of

society, in addition to preferring that political decisions favor these groups.

On the

other hand, it is intuitive that those who have Down-level ideas prefer that

the organization of society be decided by the people, in addition to preferring

that political decisions favor precisely the disadvantaged: the sick, the poor, the children, the crazy, those who suffer from abuse and violence, the marginalized and the

excluded.

Thinking

about politics in terms of verticality is more intuitive, more adequate and

smarter than thinking in terms of laterality, especially in our current

situation where those who are up in the hierarchy and those who have Up-level

ideas do not want to lose their privileged positions, they want to maintain and

perpetuate their positions of power. In order to do so, they fiercely refuse to change

the logics of the organization of society, since precisely those logics are the ones that generate a continuous increase in their power, their fortunes, their possession

over the media and their influence and power over political decisions and the laws that govern us.

The important thing to understand here is that it is necessary that we see the

left-right scheme for what it really is, nothing more and nothing less than a

convention, a historical convention which has shaped the reality of how

politics are thought about throughout nations. And conventions, as we know,

are not universal laws or norms, they can and should be changed if we realize

that they are inadequate. The Up-Down scheme seems the most evident and

intuitive as an alternative.

Rotating vertically our horizontal political scheme of thought means obviously a profound change in the way we think about politics and the things we do in it.

Rotating vertically our horizontal political scheme of thought means obviously a profound change in the way we think about politics and the things we do in it.

________________________________________________________________________

Consider supporting us so we keep bringing you more high quality and deeply insightful content.

Consider supporting us so we keep bringing you more high quality and deeply insightful content.

Comments

Post a Comment