On Ecolinguistics

By Rodrigo Cáceres

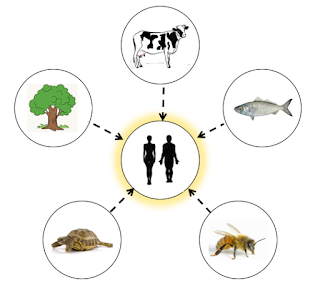

Ecolinguistics is currently one of the most productive fields of inquiry about language, since it allows us to take a broader, more encompassing perspective on language, enabling us to see how discourses that prevail in different cultures lead people to think and treat differently animals, plants and the land they live on. Ecolinguistics enable us to see for example how arbitrary it is that our western culture separates and opposes nature from culture, thus permanently banishing animals and plants from what is considered "Society" or the "community". It also renders visible how Western culture is filled with destructive discourses that shape the kinds of things westerners do: mass consumerism, global corporatism, destruction of ecosystems, climate catastrophe, and so on, that are leading to the 6th mass extinction and the consequent human self-destruction within decades.

I claim that one of the most groundbreaking works that allow us to rethink and locate ecolinguistics as a field of study is Eduardo Kohn's "How forests think" (2013). Simply put, Kohn reads the works of the american philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) in semiotics (the study of signs), which has been the most comprehensive study and theorization of signs, and he uses it as a theoretical framework for his ethnographic fieldwork in the Equatorian Amazon.

Kohn's study of Peirce's semiotics led him to understand that language is a very particular system of signs -symbolic signs- which are not operationally independent nor exist out in the void, but are sign systems that are existentially embedded and nested onto other more fundamental kinds of signs, which corresponds to icons and indexes in Peirce's theory.

This also led him to understand that social theory in Western culture is based upon the conviction that thought is equivalent to thought-in-language, with the implicit belief that the only kind of real thought is thought employing the symbolic system of signs that is language, and thus thought is believed to be exclusively human, which is a false belief. As Kohn puts it in his call for "provincializing language" :

In the West, our metaphysical mistake has been to collapse all kinds of thought into a single kind of thought: human thought. By focusing on this very special kind of thought, we lose sight of others and in fact relegate everything that doesn’t conform to it to the domain of non-thought. The result is dualism.

Dualistically separating the human from the rest of the world is pervasive and problematic. My claim is that although humans are indeed different (in large part because we think differently), that difference is housed in something greater that holds it.

Therefore, what is open for ecolinguistics does not only concern the ways that language and discourses specify the way we think and treat other living beings and the land, but it is also an opportunity to understand linguistics as a branch of semiotics: an opportunity to understand language as a system that is embedded in an ecology of signs that are not linguistic. Language is constantly interacting with other kinds of signs that are not linguistic, and as Kohn explains it, the most problematic mistake of social theory in the West has been to systematically disregard signs that are not properly linguistic.

Let's look at an example: Somatophobia (literally, aversion to the body). Somatophobia can be understood as an historical linguistic pattern of stigmatization, denial, aversion, undervaluing, fear and rejection of the body and all that is related to the body, which is based on a mind-body dualism: the idea that mind and body are two separate substances.

Susan Bordo (1995), a feminist scholar, explores how some leading Western philosophers articulated this rejection of the body in their writings. For Plato, the body was experienced as something "alien", "a source of innumerable distractions", "fills us with love, lust, fear [...] and endless foolery", "prevent us in the search for truth "," takes away the power of thinking. " For René Descartes, "the body is the brute material envelope for the inner and essential self, as mechanical in its operations as a machine, it is, indeed, comparable to animal existence." . Finally, for St. Augustine, the body was constantly an "enemy", a "prison" or "cage", a "threat" to our reasoning.

What is done by these authors must be understood as the constitution of conceptual associations that can become patterns of interpretation for a language user. Through apposition of the concept "body" with the concepts "threat, prison, enemy, foolery, brute, mechanical, alien" what is created in the one who validates or is convinced of this description is a habit of interpretation: whenever the word "body" is evoked, the associated concepts "enemy, prison, etc." all come into mind.

But one must also consider the emotionally negative connotation of these concepts. What happens in the one that is convinced of this description is that it also constructs a pattern of emotional interpretation: a habit of disgust, fear and aversion to his/her own body is constituted and amplified each time one feels "lust, love and emotions". In other words, this is a psychosomatic habit of interpretation that is originated in language, and that through semiotic processes ends up shaping the way people relate to their own experience, creating a habit of disgust towards their bodily experience, and hence towards sensations, sexuality and emotions.

This is just one example of how linguistic signs generate effects in other kinds of signs, and it can be the basis to understand that human experience is plastic and shaped through the systems of ideas that people create through language: that what which for us is natural, for example that we dwell most of the day in our heads, may be just a consistent pattern of interpretation, the consequence of a culture that has been historically obsessed with reasoning and has loathed the body. One can actually see how this happens in different regions of the world. In France, for example, home of Rene Descartes, people in general tend to be very stiff in their body movements, highly sexually repressed, usually uncomfortable when it comes to expressing affection and they tend to seem very logical and unemotional in their ways of speaking and behaving toward others.

You can find the second part of this post clicking here.

You can find the second part of this post clicking here.

___________________________________________________________________________

Consider supporting us so we keep bringing you more high quality and deeply insightful content.

Consider supporting us so we keep bringing you more high quality and deeply insightful content.

References

Bordo, S. (1995). Unbearable weight: Feminism, Western culture, and the body. Univ of California Press.

Cáceres, R. (). Somatofobia, conciencia corporal y nirvana. Link here

Kohn, E. (). Beyond Language. Link here

Kohn, E. (2013). How forests think: Toward an anthropology beyond the human. Univ of California Press.

McNabb, D. (2019). Hombre, signo y cosmos: La filosofía de Charles S. Peirce. Fondo de Cultura Economica.

Disculpa tienes perfil en academia edu o researchgate para seguir tu trabajo?

ReplyDeleteHola, para que te lleguen notificaciones de mi trabajo puedes suscribir tu mail en la página principal https://ecolinguistique.blogspot.com/. Por ahora la mayoría de mi trabajo está en los blogs. Tengo un researchgate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rodrigo_Caceres9

Delete