Our tragic fate with the metaphors of dogmatism

All of us most likely know the painful or embarrassing experience of acknowledging that we are wrong, that our beliefs were inadequate and that we must abandon them. Probably for centuries we have been conceptualizing opinions and beliefs in terms of fixed positions in space (i.e. we ask: What is your position/stance on this subject?). Our language also has a long history of conceptualizing disagreements of opinion in terms of combats: we speak of defending our position, attack the other's stance, we can win or lose the argument, and so on. Since we conceptualize arguments as combats, this presupposes that we must defend something that we value and cherish, something that is meaningful, that matters to us and which is ultimately worth defending.

Most people deeply cherish their beliefs, whether they are beliefs in God, in their political ideologies, in economic progress, in Science, Technology or any other entity. Why does this happen? Why do we become so emotionally identified with our beliefs? A synonym of belief is useful to understand this question: the concept of conviction. This concept highlights specifically the fundamentally emotional nature of belief: having a conviction about the reality of something is a deeply meaningful and emotional phenomenon.

Moreover, we talk about "holding firmly an opinion", "I hold this position" which means that we understand our opinions as objects that we hold on to with different degrees of strength. Since we said that beliefs are also conceptualized in terms of fixed positions in space, then metaphorically speaking, in this gesture of holding onto a a belief or opinion, opinions and beliefs are anchors, they are foundations, our grounds, our basis upon which we justify the actions that we do and the ideas that we have. Stephen Batchelor affirms that for the Buddha (Gotama) "the problem with holding firmly to an opinion or belief is that those who do so become “entangled in a thicket” or “trapped in a snare”" .

In general, through our beliefs/convictions we justify most of the actions that we carry out in our lives, so beliefs and principles become the conceptual "glue" that gives coherence and meaning to our existence. In other words, our subjectivity is made out of the convictions and values we hold, they become ingrained in our most deep sense of identity and self, and they give coherence to everything we do.

Moreover, we talk about "holding firmly an opinion", "I hold this position" which means that we understand our opinions as objects that we hold on to with different degrees of strength. Since we said that beliefs are also conceptualized in terms of fixed positions in space, then metaphorically speaking, in this gesture of holding onto a a belief or opinion, opinions and beliefs are anchors, they are foundations, our grounds, our basis upon which we justify the actions that we do and the ideas that we have. Stephen Batchelor affirms that for the Buddha (Gotama) "the problem with holding firmly to an opinion or belief is that those who do so become “entangled in a thicket” or “trapped in a snare”" .

In general, through our beliefs/convictions we justify most of the actions that we carry out in our lives, so beliefs and principles become the conceptual "glue" that gives coherence and meaning to our existence. In other words, our subjectivity is made out of the convictions and values we hold, they become ingrained in our most deep sense of identity and self, and they give coherence to everything we do.

Philosopher Slavoj Zizek refers to this arguing that "ideology is our spontaneous relationship with our social world, how we perceive each meaning and so on... we, in a way, enjoy our ideology [...] to step out of ideology: it hurts, it's a painful experience, you must force yourself to do it [...] if you trust your spontaneous sense of wellbeing or whatever, you will never get free. Freedom hurts."

This painful experience is due to the fact that our deepest beliefs and convictions get to our most profound sense of identity, and we know this from experience: we easily feel emotionally affected whenever somebody puts into question our most profound beliefs.

This is specially evident in religious ideologies and in their history, where identification with deities and their corresponding worldviews can go as far as justifying wars and massacres over centuries in order to defend these ideologies.

This is specially evident in religious ideologies and in their history, where identification with deities and their corresponding worldviews can go as far as justifying wars and massacres over centuries in order to defend these ideologies.

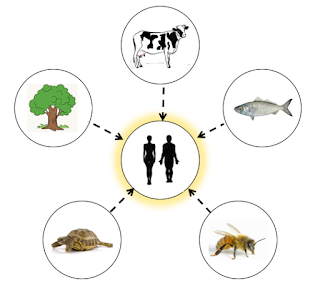

In most of the articles I have written on this blog I advance the idea that the ecological crisis is most fundamentally the consequence of an ideological edifice, a set of stories (hence, a set of beliefs/convictions) that is proper to Western culture: the opposition between Nature and Culture; the belief in an independent reality; the belief that human nature is selfishness and avidity; the idea that Nature is only a source of raw materials to be exploited; appraisal patterns such as Economic growth is good; the scorning of emotions and animals, among others.

With the context I have outlined so far, overcoming the dominant convictions and beliefs that are provoking global ecological and social disaster seems to be a colossal task: what we are facing is that a great majority of people are deeply and personally identified with their beliefs, convictions and ideologies -some of which have been around for centuries- (for example, capitalists and politicians actively looking for power and profit; consumers wanting fashionable products) and they will absolutely not want their beliefs challenged or even abandoned, since they give meaning to their sense of existential identity.

As I argued, challenging one's beliefs is usually met with utter resistance since it necessarily implies challenging one's deepest sense of existential identity, and also because these beliefs justify the actions they realize on a daily basis.

Moreover, when we think about our deepest beliefs and convictions, we normally experience them as truths, as unquestionable certitudes that reflect the state of things. Philosopher Humberto Maturana claims that "certitude denies reflection, knowledge anchors you because while you know you do not reflect [...] And we do not reflect, we do not let go of the certitudes of that which we say we know is the case...in order to look at it and see if the foundations that we have are adequate or not".

Moreover, when we think about our deepest beliefs and convictions, we normally experience them as truths, as unquestionable certitudes that reflect the state of things. Philosopher Humberto Maturana claims that "certitude denies reflection, knowledge anchors you because while you know you do not reflect [...] And we do not reflect, we do not let go of the certitudes of that which we say we know is the case...in order to look at it and see if the foundations that we have are adequate or not".

This seems to me as the most tragic aspect of our ideological predicament. The first aspect of it is that our culture has historically conceptualized opinions as fixed positions in space that we hold on to, positions that serve for us as anchors and as precious objects that one has to defend. The second aspect of it is that since we are beings that naturally look for meaningfulness, in our culture this meaningfulness is grounded on the kinds of conceptualizations I mentioned, which lead to the fact that we passionately cherish our beliefs and convictions and fiercely resist losing them.

Added to the the fact that ideologies/stories are hidden, that is, that we don't naturally notice them as such, and that we experience our discourses as fitting the world directly, this puts out an even grimmer perspective to our current predicament.

Added to the the fact that ideologies/stories are hidden, that is, that we don't naturally notice them as such, and that we experience our discourses as fitting the world directly, this puts out an even grimmer perspective to our current predicament.

_______________________________________________________________________

Consider supporting us so we keep bringing you more high quality and deeply insightful content.

Consider supporting us so we keep bringing you more high quality and deeply insightful content.

Very nice writing. Excellent.

ReplyDeleteHello, thanks for this. I also read your blog on ecolinguistics. You seem to be part of the gathering recognition of a set of links between systems theory, the body, provisional thinking and ecological concern (or negatively between linearity, dogmatism, abstracted beliefs and trashing the planet). You might be interested in the work I and others have been doing at www.middlewaysociety.org. I also wonder if you are familiar with embodied meaning theories (Lakoff and Johnson), and with Iain McGilchrist's book 'The Master and his Emissary'? Each of these sources give linguistic and neuroscientific accounts respectively of the sources of dogmatism: linguistically in the failure to recognise the dependence of meaning on metaphors and schemas rather than representation, and neuroscientifically on the over-dominance of the left hemisphere, specifically the pre-frontal goal-oriented and representational regions, over the wider areas of the brain that give meaning its basis in the body. My own work on the Middle Way draws on these as well as Buddhist practice, focusing especially on the idea that it is not so much what we believe as how we believe it (dogmatically/ abstractly/ metaphysically/ without alternative options) that causes major problems in human judgement of which the ecocrisis is one result.

ReplyDelete